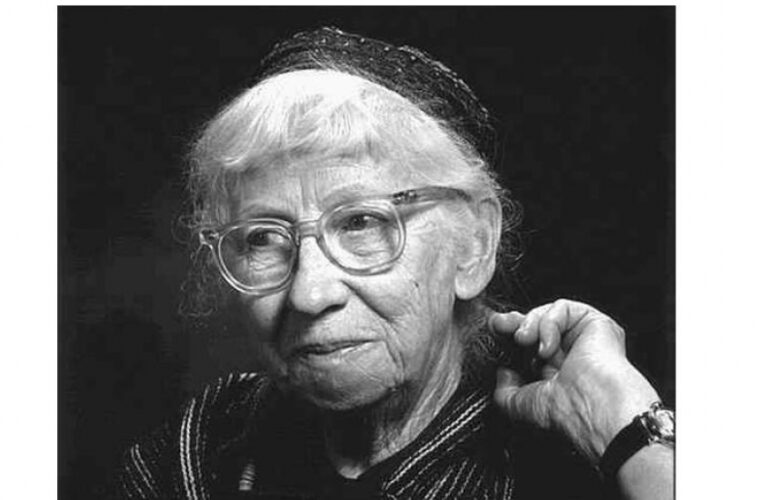

Imogen Cunningham was born on April 12, 1883 in Portland, Oregon and died on June 24, 1976 in San Francisco, California. A photographer at the center of the 1920’s photography revolution, Imogen Cunningham paved the way for female photographers through her experimental and complex black-and-white film craft. She practiced film photography starting with portraiture and expanding all the way to nature shots and experimental double exposure pieces. She is famous for photos of nude women by water in hazy surroundings and the geometric shapes that she pulled from her garden.

Cunningham began her photographic practice with a financial focus as an adult. She photographed members of her wealthy Seattle community, and the income kept her afloat. At this point in her career, she could not afford as many creative risks, such as light, shadow, and controversial subjectivity. Later in her life, however, as she became more comfortable financially, Cunningham was able to break out of the box of traditional portraiture and began developing her iconic style.

That iconic style began with platinum prints from a 5×7 camera. Platinum prints allow for a range of rich browns, reds, blacks, and greys in the photo and create prints that can stand the test of time, retaining their true colors. This process of printing dries almost matte, meaning that the images are more delicate and less glossy than silver prints. Cunningham had the upper hand on other photographers with this complicated and finicky process because of her background in chemistry. She did, however, stop printing in platinum early on due to the expense of the material. Cunningham always kept her equipment simple: she used a collapsible tripod, film camera, and twelve glass plates.

Cunningham’s family, which was not very wealthy, recognized her talents and passion early; they encouraged and supported her craft as much as they could. Her artistic study began at a Saturday art school. The specific art school name could not be determined. She went on to attend college at the University of Washington, where she began to hone her skills in still lifes and portraits. There in Seattle she was also both a member of the Seattle Fine Arts Society and a photo technician for Edward Curtis, a well-known photographer famous for his portraits of Native Americans. This early professional connection helped her to make others later in her career.

Cunningham graduated in 1907 and was awarded a grant to go to Dresden, Germany to study photographic chemistry, but she decided to return home after only completing a year of the program — believing that she could not do both science and photography. She made a detour to meet East Coast photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who turned into a big fan of her work and introduced her to Gertrude Käsebier, a successful and famous female photographer. Inspired and motivated by these two individuals, Cunningham opened her own studio in Seattle and began to experiment with artistic photography in addition to the portraiture that supported her. In 1914, she had a major public launch with her first solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

Cunningham moved to Oakland in 1920 when her husband, Roi Partridge, took a position teaching art at Mills College. Partridge was an etcher, creating mostly landscapes, and he was later named the first director of the Mills College Art Museum. While in Oakland, Cunningham abandoned most of her professional photography work for motherhood, and it was this move that allowed her to explore the subject matter and style that made her iconic. She turned her camera from strangers to her family and their garden, capturing her sons as they grew up and experimenting with the shapes and shadows of plants that she grew at their home on Harbor View Avenue. This home in the Redwood Heights neighborhood had a bay view and was an oasis of sorts in the middle of a city experiencing an economic/industrial boom in the 1920s. During her early years in Oakland, Cunningham did not venture much into the artist community around her but did spend quality time in the buildings of Mills College’s dance department, where she captured photos of the dance students. The Bay Area community at this time might have known Cunningham’s work from the Mills College store, where her prints were sold for a mere five dollars (Cunningham).

In her later years, Cunningham founded Group f/64 with Ansel Adams and Edward Weston — the former whom she believes that she met through the Mills community. The group, named for the smallest aperture setting on a large-format camera diaphragm, was founded in 1932 and rebelled against pictorialism — the dominant late- 19th- and early-20th-century style focused on projecting emotional intent through photos. This group of Californians practiced highly detailed, sharp-focus photography; they were a group of modernists. Over the years the group secured exhibitions to promote their style of photography as well as to promote other artists who were pushing the boundaries of photographic art. The group defined the next generation of photography in stylizing “pure” or “straight” practices. This style of “pure” representation is greatly reflected in Cunningham’s work as her style developed and matured throughout her life. Group f/64 occupied galleries, including but not limited to San Francisco’s de Young Museum, where the group had their first exhibition together.

The group was almost a contradiction in and of itself: it was politically progressive in some ways, with women being substantial in their membership and influence. However, some of the male founders were philanderers and “role models” in womanizing for younger male artists. Cunningham took issue specifically with these actions. In the 1940s the group began to drift apart as some artists started to focus on subjects that did not fit in with the apolitical formation of the group. Group f/64 members moved across the state and country from Los Angeles to New York but kept in touch, kept practicing, and held the group’s purpose and method alive in the hope of cementing the style into 20th-century photographic practice.

Cunningham moved to 1331 Green Street in San Francisco in the ‘40s following the dissolution of Group f/64. This turn-of-the-century home, sandwiched between two taller buildings in the Russian Hill neighborhood, would be her home until she passed away in the ‘70s. She was in San Francisco for the Summer of Love, the height of the Black Panther Party’s activism, and the Vietnam War. This environment can be seen through photographs that she labeled Street Scenes.

Imogen Cunningham was a woman of influence in the arts scene on the West Coast with an arm that reached across the country and all the way to Europe. The breadth of her work covers portraiture, landscapes, documentation of certain snapshots in time, and experimental art prints. As an Oakland artist, she called the city home in the crux of her movement into the public eye as a well-known photographer; it was the place that her children called home. Oakland was the space where she was enabled to help launch a century-altering movement in photographic art.

Haunts:

- Mills College (5000 MacArthur Boulevard, Oakland, CA 94613), where Cunningham’s husband taught art and was the first director of the Mills College Art Museum.

- Her residence on Harbor View Avenue in the Redwood Heights neighborhood.

~ by Camille Brown ~

External Links:

“BIOGRAPHY: IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM (1883–1976).” The Phillips Collection, https://www.phillipscollection.org/research/american_art/bios/cunningham-bio.htm.

Blaustein, Jonathan. “An In-Depth History of Group F.64.” The New York Times, 11 Dec. 2014, lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/12/11/an-in-depth-history-of-group-f-64/.

Cunningham, Imogen. “INTERVIEW: ‘Oral History Interview with Imogen Cunningham – June 9th, 1975.’” American Suburb X, 1 Jan. 2019, https://americansuburbx.com/2009/01/interview-oral-history-interview-with.html.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Brittanica. “Group f.64.” Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Inc., www.britannica.com/art/Group-f64.

Kramer, Hilton. “Imogen Cunningham at Ninety: A Remarkable. Empathy.” The New York Times, 6 May 1973, www.nytimes.com/1973/05/06/archives/imogen-cunningham-at-ninety-a-remarkable-empathy.html.

Image 1 – Cunningham is famous for her nudes. This early example of her nude photographs highlights the interaction between a man and woman. When photographs of naked bodies were considered fringe, the photographing of a man and woman together illuminates Cunningham’s rejection of social norms in her art.

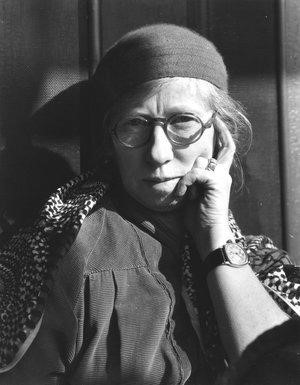

Images 2 and 3 – Portraiture is where Cunningham began. These are both later portraits, but they highlight her ability to capture more than just the face of a subject but also the environment and space around them. Most of Cunningham’s earlier portraits are hard to find purely because they were done on commission and therefore belong to individuals in private homes.

Image 4 – This photograph of a woman bridges the gap between human and nature and highlights Cunningham’s ability to use multiple exposures to create other-worldly themes in some of her photos. She also does this through the creation of auras in some of her portraits.

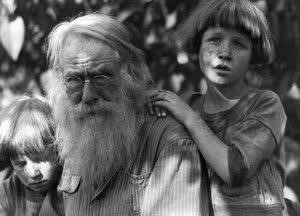

Images 5 and 6 – Cunningham often turned her camera on her family. In the photos where her family are the subjects, Cunningham uses a softer, less experimental style. Her family became her subjects more and more when her sons were young — this was during her time in Oakland. Her photos of her family are unique to Cunningham as they seem to have no intention other than to capture a moment in time. This is owed to the simple set up and style of the photos and the depth of blacks used in printing, making the images softer.

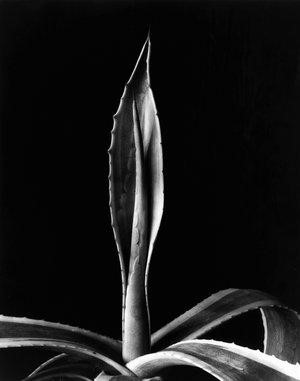

Images 7 and 8 – While in Oakland, Cunningham developed her famous style of plant photography; sharp contrast and simplicity are part of the signature style of Cunningham’s nature pieces. This was also the time when Cunningham began to experiment with nature in conjunction with people. Photos, such as the one on the right, bridge the gap between nature photos and photos of human subjects through experimentation with shape. The image on the left captures Cunningham’s ability to use simplicity and framing to create a stark image of a singular subject while still maintaining the natural beauty.

Image 9 – Another part of Cunningham’s art was portraits of dancers — a lot of the time taken at Mills College. These photos are technically portraits, but they rely on the use of shadow and shape to create contrast and crispness in the foreground and background as well as to highlight the movement of the human body.

Images 10 and 11 – As also mentioned previously, Cunningham is also well known for her nudes. At a time when women’s naked bodies were still considered scandalous, it was even more unexpected to have a woman as the photographer. Cunningham photographed naked women and men, which had many themes and styles. One style, as pictured through her photo of her husband, Roi Partridge, again shows human interaction with nature; another, as shown through the two women, plays with shadow and shape.

Images 12 and 13 – Lesser known are Cunningham’s Street Scenes. This photo of a young black boy comes from the streets of San Francisco. Her street scenes are more raw and crisper than the previous portraits shown, but they parallel her photos of her family in creating a familiarity to the subject through framing and printing technique. The second photo of the women is from Haight Street, the home of the famed Summer of Love.

Images 14 and 15 – It is fitting to end with this second self-portrait as Cunningham was not always a serious person. This photo captures this side of her personality in a way that only she could.